Colonialism and Landscape

The Unsettling History Behind Early American Landscape Paintings

Upon glancing at a landscape painting depicting American scenery, what is the first thing that catches your eye? Is it the rich hues showing scenes of verdant forestry or sparkling streams? The light paint strokes used to create wispy clouds and tall trees? More often than not, we, as viewers of art, tend to enjoy the aesthetics of a piece before knowing the story behind what we are looking at. It is natural to enjoy these paintings for what they are at face value; it can be easy to miss the meanings and histories behind the canvas. This can be espeically true of the way we view American landscape paintings. We often enjoy the talent of the artists and their creations before we understand the scenes depicted.

Unfortunately, as with the history of many Western nations, America has a darker history to it that can be missed when we take things in at only the surface level. By analyzing Delaware Water Gap painted by George Inness, we can see the ways in which early American art covered up the colonial violence in the Americas in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I intend to argue that early American landscape paintings are not good representatives of the serenity and peace that they depict by analyzing nineteenth century scenery painting Delaware Gap by George Inness and the history of the land it depicts in order to show how European settlers masked the truth of the harm and suffering done on Indigenous groups within America through these patriotic paintings.

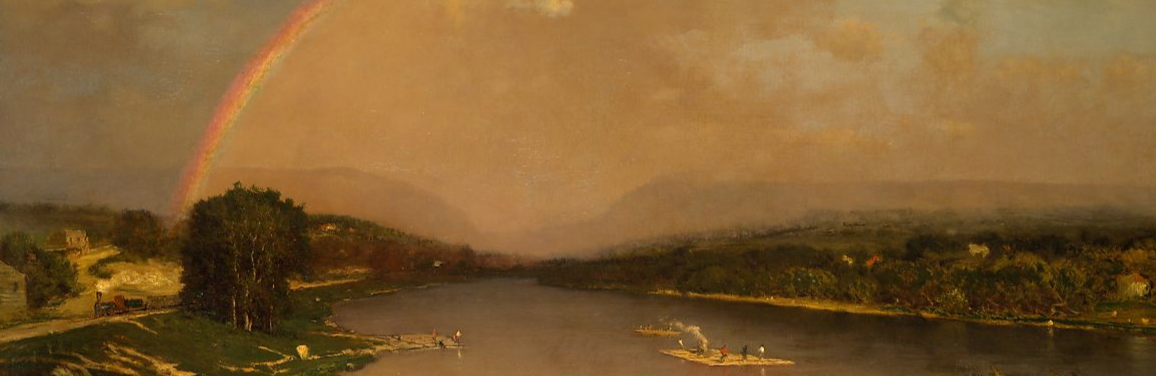

Fig 1. Inness, George. Delaware Water Gap. 1861. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Delaware Water Gap (see fig. 1) was completed by George Inness in 1861. It was one of many views Inness painted of this river area, many of which are all entitled the same name. (Although he has many paintings by the same title, this specific Delaware Water Gap is not to be confused with Inness’ other Delaware Gap paintings.) Inness painted this scene using oil on canvas, the oil paint allowing for there to be a textured look amongst the clouds and the greenery.

At the time of westward American expansion, landscape was a common tool for artists to help depict what lie ahead of settlers and to give them an idea of what the land beyond their homes looked like. The UK National Gallery states, “in the 1850s, much of the American Landscape was still unknown to European settlers. Inness gives it a distinctly European look to suggest fertile land that can be easily inhabited and cultivated” and describes the landscape as “tranquil and domesticated” (National Gallery). This was important for Inness to depict the land as calm, giving it a welcoming look that implored settlers to see it for themselves in order to help encourage American expansion.

Inness accomplishes this peaceful look within this landscape painting by having nature appear very friendly. The main focus of the painting is on both the water and the green land next to it. On the land, a luscious green grass area, there are cattle grazing both on the grass and in the water. There are humans depicted in the scene, both on the grass and on the barge that is floating down the river. Both the frolicking humans and animals within this painting gives it the sense that it is very inviting and a very calm and restful location. The mood these animals and human creates seems very inviting, as if they are begging the audience to come join them to live a relaxing life just like them on these new territories.

This peacefulness is matched by the nature surrounding the animals and humans. Most prominently, there is a rainbow surrounded by soft, wispy clouds: the sign that rain has just passed, a storm has just blown over. The curve of the rainbow directs the viewer’s eyes to travel upwards to where there is a light in the clouds, a sign that the sun is gracing this area with its light, basking it in a warm glow. This adds to the peaceful, serene scene by showing how nature is very friendly, making the area look overall inviting.

In Cultural Contact and the Making of European Art since the Age of Exploration, Julie Hochstrasser offers us perspective about the correlation of landscape paintings and colonialism in her chapter Remapping Dutch Art in Global Perspective. Hochstrasser discusses the hidden truth of Dutch colonialism in Dutch landscape paintings and offers a fresh insight into how these paintings hide the painful truth of European imperialism. By using the specifics of Dutch art during mainly the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Hochstrasser shows the ways in which the culture’s art often reflected only the more glorious aspects of the culture during this time, such as expedition and trade. While this is important to reflect the good of one’s culture, Hochstrasser notes how this leaves out much of the bad the Dutch were doing when in contact with other cultures.

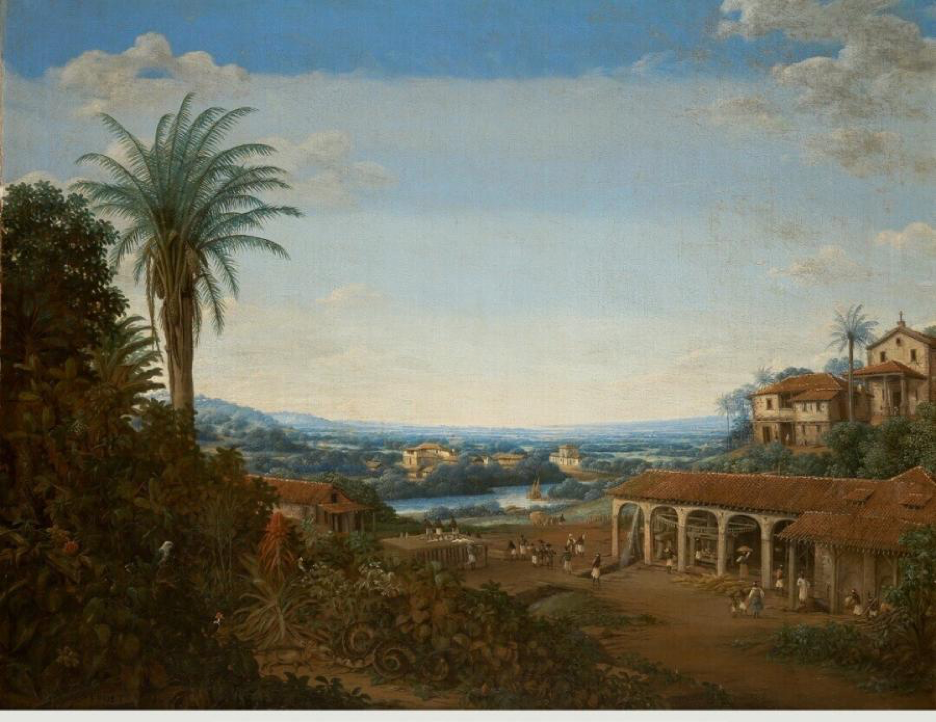

When describing the ways in which Dutch art is historically studied, Hochstrasser states, “most studies of Dutch art have until recently focused on themes and issues indigenous to the Dutch Republic on its home shores” (Hochstrasser 43). With this, Hochstrasser is acknowledging the fact that the Dutch art during this time was very Eurocentric: the art depicted subject matters that those who lived in Europe, especially those native to the Dutch Republic, would have been comfortable with and enjoyed consuming. Unfortunately, this means that there was subject matter that was less comfortable and pleasant to be viewed by a European audience. To showcase this, Hochstrasser uses the example of The Sugarmill (see fig. 2)painted in 1653 by Frans Jansz Post.

Fig 2. Post, Frans Jansz. The Sugarmill. 1653. Oil on canvas and panel. Museum Boijmans Van

Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Hochstrasser explains, “landscapes Post painted included sugar mills in scenes that are sun drenched, sleepy, and almost pastoral in feeling. But this is impression is radically at odds with the real facts of sugar plantation” (Hochstrasser 56). The reality of these sugar mills included “perpetual violence and warfare” an “entailed the large-scale importation of slaves from West Africa to the Americas” (Hochstrasser 56). While on first glance The Sugarmill seems to be a harmless painting depicting an idealist scene to European expedition and trade, there was a dark truth hiding behind it that was not made explicitly clear. Instead of showing the grave reality of the Dutch hegemony of Brazil on this plantation, it shows the plantation in a way in which was palatable and comfortable for the Europeans back home to view.

This idea is not unique to just the Dutch. Using Hochstrasser’s perspective about landscape paintings can allow us to analyze art of all cultures more critically. Hochstrasser’s idea that a culture’s art can leave out much of what was happening behind-the-scenes can also be applied to early American art, especially when it comes to art from the American colonial period. While American landscape paintings can offer seemingly harmless depictions of beautiful scenery, they fail to depict the violent colonial history waged on groups of peoples Indigenous to America upon the arrival of the European colonizers.

Delaware Water Gap depicts what is now identified as the Delaware Water Gap, located on the border of Pennsylvania and New Jersey. There were three distinct groups indigenous to this land in this area at the time of Inness’s painting: the Lenape, “Jerseys,” and Munsee (Becker 116). However, colonization harmed these groups, as they were forced to move away from their native lands to make room for European colonizer expansion into North America, resulting in Native displacement. In the first ever treaty between the newly self-declared United States and Indigenous groups within the new states, the Fort Pitt Treaty of 1778, the United States made agreements with these Lenape tribes indigenous to Delaware whose land was depicted in Delaware Water Gap. Some of what this treaty called for was “perpetual peace and friendship,” “forgiveness of grievances,” allyship between the Delaware Tribes and the United States against the British, and the United States’ recognition of Delaware sovereignty (Zotigh). This promise of peace and friendship and what it would have looked like can be seen in Delaware Water Gap through the way Inness uses nature to look inviting. From the rainbow, to the people and animals lazily relaxing and grazing, to the overall soft, dream-like feel the painting encompasses, there is no indication within the painting of the dark history this piece of land and water has.

This promise of peace within Delaware did not last, however. According to the official organizational website of the Delaware Tribe, the indigenous groups were pushed away from their homelands and forced to leave because of the “misleading treaty agreements and the threat of military force” resulting in these groups “[abandoning] their remaining homelands and [moving] west” (“Removal History…”). Furthermore, in the early 1790’s, the United States “launched a series of military operations to crush [Native] resistance” (Ostler 591). The indigenous Delaware Groups, as well as all other Native American groups, were not treated in the ways in which their treaties promised they would be. This violence took place about sixty years before Inness painted Delaware Water Gap, but the violence continued on as American expansion kept pushing west onto the territories the indigenous groups were forced to flee to. However, this cannot be seen through the vibrant, dreamy colors of the Inness’ Delaware Water Gap. The land is shown, but the horrors that occurred on the land and to the people indigenous to the land are not shown. Just like how Hochstrasser comments on The Sugarmill and how Post creates a “sleep” and “pastoral” feeling within his paintings while covering the horrid truth of the work being done by enslaved Brazilians, Inness creates a peaceful feeling within his landscape while the mistreatment it took to get to that point are unbeknownst to the audience.

While landscape paintings can beautifully depict land, there may be some other hidden truth behind them. In the case of early American history, it can be seen how these landscapes covered the horrors of what took place on these lands in favor of making the land look appealing to European and American expansion. By analyzing nineteenth century scenery painting Delaware Gap by George Inness and the history of the land it depicts, I argued that early American landscape paintings are not good representatives of the serenity and peace that they depict in order to show how European settlers masked the truth of the harm and suffering done on Indigenous groups within America through these patriotic paintings. ✧

Something you loved about this piece? Questions, comments, concerns? Let me know!

Post a comment